Pump jacks still rock slowly up and down, pulling oil from the fractured rock deep below the surface. These workhorses of the oil patch were brought in herds by hordes of oilfield workers, roughnecks, drivers, drillers, geophysicists and wildcat prospectors seeking their fortunes in the fields of “Saudi America.” Fueled by a market paying $100 and more for a barrel of stinking black crude and investors looking for ventures offering some prospect of yield for the funds they had evacuated from the housing market after the financial collapse of 2008, the oil and gas boom brought an influx of support industries to the towns around the oil and gas formations, electrical distributors among them.

For a couple of years, the activity was intense. Construction of “man camps” to house the workers, hotels, restaurants, shopping centers and schools exploded. Local electrical contractors found themselves competing fiercely with firms from out of state, but there was work enough for everyone. Distributors from distant towns opened new branches to serve the oilfield boom, supplying everything the drillers and frackers and production teams and all the construction crews building new facilities might need. Distributors already well established in those areas saw a windfall of significant scale.

“We did about $50 million out of our San Antonio location. Of that, about $15 million has come from the oil business,” says Chris Petty, area manager for Elliott Electrical Supply’s operations in the Austin and San Antonio, Texas, area. “We were selling everything from switchgear and lighting through Crouse-Hinds industrial fittings, rigid pipe, wire, cable tray, all the components. We have three stores in the Eagle Ford shale serving all segments of the oilfield.”

When the price of oil began to fall in June 2014, the impact wasn’t felt right away out in the field. The price of oil is inherently volatile, depending on a mind-boggling global mix of influences from fundamental supply and demand to interest rates, the value of the U.S. dollar and the caprices of international politics. Brief moves sharply up or down are eyed warily and then dismissed by exploration and production firms who must base their decisions on the longer time horizon that aligns with the life cycle of a well. As the price continued to decline through the end of 2014 and swing producers who could support the price by curtailing production chose not to, a feeling familiar to long-time denizens of the oil patch began to set in.

The price of a barrel of benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil on June 20, 2014, the first day of summer, was $107.26. Those were sunny days. By the day after Christmas the price was $54.73. It continued falling from there into the mid-$40 range, recovered to $60 by summer 2015, then resumed its descent, dropping below $30 briefly in January and February this year. At press time, the price is around $45.

“We started to notice a decline at the beginning of last year,” Petty says. “For a while it was just slow and steady. Then it turned to a steep decline the last four to five months.”

A turn in the numbers

During the boom years North Dakota ranked among the fastest growing states in the United States. Now it’s near the bottom, and it’s not alone, according to a recent report by economic research firm IHS Global Insight.

“North Dakota went from the second-fastest growing state in 2014 to the slowest just a year later,” the firm’s Karl Kuykendall, principal economist, wrote. “Texas fell from fourth fastest in 2014 to 28th last year, trailing U.S. growth for only the third time in the past 25 years. Employment declined in Wyoming, West Virginia, Louisiana and Oklahoma, with Alaska and New Mexico barely squeaking out gains. The stark impact on total employment made it very clear how significant a role the oil and natural gas industries have on the broader economy of energy-producing states.”

Dakota Supply Group, Fargo, N.D., has operated branches in the western North Dakota oil patch towns of Williston, Bismarck and Minot for years, so they were already well placed to serve the influx of demand. The company opened a new branch in Dickinson, a move it had in the works already before the oil boom came, says John Gearman, the company’s electrical and automation segment manager.

“When we started it was a scramble to get enough people out there and to keep up with what was going on,” Gearman says. “Today, it’s down. A lot of oil companies have packed up and moved out, a lot of out-of-state contractors have gone. At the beginning of this year, I looked at the oil companies that are working out there, I looked at their budgets, and they were cutting them by 80 percent.”

Behind those numbers lie the impacts of changing fortune on many people’s lives. Oil producers that were leveraged beyond their shrinking cash flows shed assets, laid off workers, offered themselves up for sale to larger or better-funded players or declared bankruptcy.

Deals large and small have gone sideways, including a proposed mega-merger between oilfield service giants Halliburton and Baker Hughes, valued at $28 billion, which was cancelled at the end of last month, citing “challenges in obtaining regulatory approvals and general industry conditions that severely damaged deal economics.”

The real impact on the ground, away from the boardroom deals, has been seen in the exodus of all the out-of-state workers, empty hotels and restaurants, and projects left incomplete.

“It’s been hard on that local economy, the small towns, which built up very fast,” says Petty of Elliott. “Most of them were smart enough not to get used to the additional tax base, so they will be fine, but it has a different feel than it did before.”

Electrical distributors serving the oil-producing regions have been forced to reconfigure their businesses at those branches to match what the remaining flow of business justifies.

“We’ve had to expand our circle a little,” Petty says. “At all three locations we bought the land and built our own facilities, so that has helped. We reduced headcount and tweaked our inventory to a reasonable amount of money invested for what we’re moving. All three locations are still profitable, but they’re a long way from what they were.”

Now what?

Just by the inherent nature of the oil business, if the price recovers the oil people will return to drill again. The recent recovery in crude oil prices from below $30 early this year to around $45 now has some industry analysts and investors declaring that the bottom of the price curve is now behind us and after a flat period in which supply and demand regain balance, prices will again begin to rise.

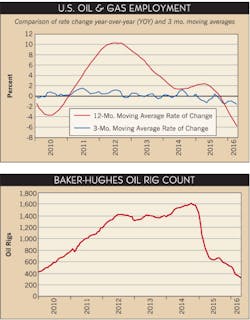

Analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ national employment data for the oil & gas market finds that since late last year the pace of the monthly declines in employment in this niche are increasing rather than bottoming out. The decline in the rate of change in the 12-month moving average for oil & gas employment is actually worse than the decline in the three-month moving average. The longer-term rate-of-change trend crossed below the three-month trend on Nov. 15 — a dismal scenario that stock chart analysts call the “death cross.”

The news isn’t much better right now in the rig count data. It reflects huge year-over-year declines as drilling activity is down in many areas by 40% to 60% year-over-year. U.S. rig counts have dropped to their lowest level in the 67-year history that this series has been tracked, says IHS Global Insights’ Kuykendall, and they continue to trend lower, plummeting 78% from late October 2014 to mid-April 2016. “Texas, which alone accounts for close to half of total U.S. land rigs, has seen rig counts drop by a similar pace as the nation; rigs in North Dakota, the second-largest oil producer, have been hit even harder, down 84% due to a slump in activity in the Bakken region.”

According to an April 20 release from the Energy Information Administration (EIA), “In response to continued low oil prices, onshore crude oil production in the Lower 48 states is expected to decline from an average of 7.41 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2015 to 6.46 million b/d in 2016 and to 5.76 million b/d in 2017. Increased production from the Gulf of Mexico is not enough to offset those declines, with total projected U.S. production falling from 9.43 million b/d in 2015 to 8.04 million b/d in 2017.”

A real production cut by U.S. oil companies adds to the prospect of a price recovery in the wider market. At the same time, U.S. oil producers have slashed their operating costs to the point that they can generate positive cash flow at a lower price point. They also are ready and able to bring more production back on in an instant if the price permits.

“There are close to 1,000 wells they’ve already drilled that are capped,” Gearman of Dakota Supply Group says. “They can bring those on fast when price goes up. The real work is done, it’s just a matter of bringing pumpers in and bringing electrical and mechanical equipment out to the sites.”

Meanwhile, electrical distributors active in the oil-producing regions are concentrating on capturing all they can of the work that’s still being done.

Gearman of Dakota Supply Group says the local contractors who had been long-time customers were hammered during the boom by insurgent out-of-state contractors who moved in. With those contractors now gone home, the locals are regaining their share of the market.

Petty of Elliott says his oilfield-serving locations have shifted their emphasis to serving other industries. “We’re calling on the commercial work that’s available. Any construction going on. We’re still close to Laredo and Corpus Christi, so there are still customers we can call on that are not strictly tied to oil.”

Some reassuring truths help oilfield suppliers keep perspective. The oil is still down there. The world still runs on oil. So presumably when the price is right the bustle of the oil towns will return. But there’s no telling when that might be.

Although U.S. producers have lowered their costs and can ramp up production quickly, that responsiveness also keeps a lid on how high prices can go, barring some kind of disruption in the global market.

Added to that, the post-recession resurgence of the U.S. oil industry based on wider application of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has not gone unnoticed in other countries around the world where tight shale and other stingy but oil-rich geological formations might be turned to gold when the price permits.

Therefore, the next oil boom may not lift the oilfield towns to the heights they saw in 2014. But like the oil fields, the electrical distributors are still there and when the time comes, they’re ready to go again.