Sponsored

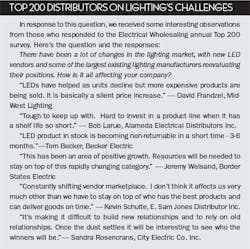

The wondrous changes brought by LED lighting technology over the past few years — the ability to offer your customers a product that provides better lighting along with dramatic reductions in energy and maintenance costs over a longer product lifetime with far better control than they ever had available before — also bring with them a fiendish set of puzzles for distributors to solve in terms of inventory.

“One of the challenges is that things now have a shelf-life,” says Rock Kuchenmeister, president of K/E Electrical Supply, Mount Clemens, Mich. “I like to tease manufacturers (in inventory-stocking discussions) that it’s just cash. All we’re doing is turning cash. It’s just like selling bananas but it’s bananas that don’t rot.

“Well, now they rot.

“For most of the products we sell in the electrical industry that’s not true,” Kuchenmeister adds. “Take 2.5 inch conduit for example. If it sat on my shelf for a year, I wouldn’t like it, but I can sell it. With LEDs and the rapid changes, now we’re getting into a situation where distributors have to think about shelf-life. How long can I hold it? Do I need to unload it like clothes going out of style?”

The flipside of the puzzle is just as tricky. Distributors must nurture along the traditional lighting technologies through their declining phase, technologies they have sold for generations that are installed, familiar and reliable inside and outside most buildings the world over. Shipment figures for incandescents, linear fluorescents, high-intensity discharge (HID), halogen and all the rest show them giving ground to LED replacements, but those old technologies still have significant share of market and those customers still need their tubes and bulbs. For how much longer? No one knows.

For a typical full-line electrical distributor, lamps account for about 5%-6% of annual sales and fixtures another 17%, according to our latest research. That doesn’t break out the growing segment – likely to become prevalent over the medium to longer term – where LED light sources are included with the fixture.

In general terms, distributors tell us they’re trying to keep shelf stock smaller and under tighter control and concentrating on turning stock faster. “Our stock levels are lower than they were five years ago,” says Steve Espinosa, president of The Lighting Co., Irvine, Calif. “It’s now about 15% to 20% less. We stock about half as many C items, and tend to buy those as needed instead of having them on the shelf.”

Lighting that rots

A story in The New Yorker last month traced the lighting industry’s curious history with regard to product obsolescence, retelling the story of Phoebus, the lighting cartel that started in 1924, in which the largest manufacturers agreed to produce lamps that burned out after 1,000 hours, one of the earliest examples of deliberate planned obsolescence.

Today, though, the cycle of obsolescence is driven not by collusion but by competition. It’s the great race to introduce lighting that is better — more versatile, more beautiful and cheaper to own and operate. The question that arises for distributors is who among their vendors can help them win.

“Traditionally our strategy has been to stock products from major manufacturers,” says Michael Fromm, CEO of Fromm Electric Supply, Reading, Pa. “Since we support most of our customers on an ongoing basis, it’s important to provide products that have the appropriate approvals and that will perform to agreed-upon specifications.

“With the pace of change in LED technology, the majors haven’t been as nimble as we’ve needed them to be. That may be a function of their size and speed to market capabilities, or they may want to vet the technology more completely before introducing it to the market. It may be strategically important for them to let others fail first. But the result is we’ve had to introduce new vendors into our roster.

“It’s common knowledge that the minute you buy a computer you’ve bought obsolete technology. Today’s lighting business is approaching that point. With the accelerated pace of change, we’re less apt to invest huge sums of capital in inventory we know is going to be obsolete within months. We’ve also had to change our approach to negotiating deals with suppliers to include guaranteed sale and other terms that give us confidence that we’re not going to be sitting on obsolete material.

“Vendors have changed their expectations too. I sat with a supplier just a few weeks ago who began his pitch with a promise of guaranteed sale (where at a pre-agreed time if the product is rendered obsolete or isn’t going to fit the niche it was intended for, they will take it back, no questions asked). Before, that was always an afterthought and even a sticking point. No supplier wants that to be their lead offer but they know distributors need the escape hatch.”

For most distributors guaranteed sale agreements are few and far between, though. The manufacturers feel the same urgency to get the existing products off their shelves to make way for the next iteration. The best core approach, say distributors, is to emphasize communication — working with vendors to get as much advance notice as possible when an existing line will be superseded by a new one.

This is the main tack Peninsular Electric in West Palm Beach, Fla., takes with its primary lamp supplier, Westinghouse, a relationship it has built recently after years of cycling through the majors – GE, then Philips, then Osram Sylvania. “We originally thought Westinghouse was a band-aid solution, but it’s been good for us over the past three years. They listen, they battle along with us about obsolescence and price changes,” says Langdon Scott, Peninsular’s senior vice president, business development. “We said with Westinghouse, ‘Keep us in the mix. We’ll keep some products on hand. Coach us so we can sell down what we have and be prepared when the new technology hits the street.’”

But the vendors are facing the same challenges of not wanting to have outdated material on their shelves. And the competition they face is shifting as well. Distributors are adding new suppliers to broaden the range they have on offer, even those who would prefer to keep their support strongly behind the majors.

“It’s forced us to have some difficult conversations with our vendors,” says Fromm. “When the demands in the market are outpacing the major manufacturers’ ability to get technology into the supply chain, it challenges the status quo of certain long-standing relationships.”

The newcomers are a mixed bag in terms of technological innovations as well as their sophistication about the electrical distribution market, distributors say. Many enter the market trying to sell direct to end users, and some learn the hard way about the value provided by distribution. “Others have studied the market and understand that distributors have an intimacy with customers and are playing a consultative role that can make them an effective way to get the technology into the market,” Fromm says.

Construction and maintenance

How LED lighting technology affects your inventory depends in part on the balance you strike between the new construction and maintenance, repair and operations (MRO) markets. For example, when supplying lighting for a construction project the customer absolutely has to have the product when and where he needs it so he can do the work, while an MRO buyer may be willing to wait to get a better lamp or a better deal before restocking the shelves of his parts crib.

For new construction, LEDs are having an impact on specifications. “The specification community generally doesn’t dwell on specific brand name lamps because in essence there are not as many lamps as we go forward in the next generation of products. They’re all fixtures,” says Scott of Peninsular. “With a specification written around, say, an Acuity fixture package, the distributor is required to provide spare parts, which in the case of LED means spare drivers, like 10 per 100 fixtures, or retrofit trim for recessed cans. You’re not providing a case of lamps anymore.”

Some distributors say they’ve seen a shift in their relationships with the independent manufacturers’ rep agencies in the lighting market, where the long-standing relationships and the value of limited distribution seem to be weakening. The longevity of new lighting systems creates more of a winner-take-all dynamic. Limited distribution is harder to sustain when walking away from an order — whether it’s over unrealistic pricing expectations or a bad lighting job you don’t want to be associated with — means giving up future potential for a longer period. As a result reps are willing to support a wider variety of distributors to avoid losing the sale.

At the same time, the role of the lighting rep in keeping distributor salespeople up-to-date on new lighting technology has increased significantly, says Kuchenmeister of K/E Electrical. “Rep agencies that support us are doing an excellent job keeping our people up-to-date,” he says. “Reps come in two to three times a year; this year we’ve already had 144 “lunch & learns,” just in lighting. The change in that regard since five years ago is tremendous.”

On the maintenance side, LEDs are changing everything. The technological advances that have improved lighting’s life expectancy by an order of magnitude are disrupting the steady flow of replacement lamp sales. The sale you make today on a new LED lighting system means you say goodbye to 10 to 15 sales of replacement lamps over the following years.

Stocking components for repairs becomes a bigger challenge as well. Lighting maintenance contractors face some of the “Maytag Repairman” problem, and in some cases increased costs. Take the job of maintaining lights on poles in a parking lot for an example. The maintenance person used to have all these interchangeable parts and could tell by the color of the light from the ground which kind of light it was. He could then go up on the lift with the parts he needed and work on it until he got it lit. Now he can’t tell from the ground what the fixture is, so he has to go up there first and find out, then determine whether it has replaceable components at all, then obtain the parts or replacement fixture he needs, then go back up on the lift to do the work.

Connected smart lighting can help with that problem, of course. Lighting systems’ emerging role as the backbone for the Internet of Things is adding more push to the pace of product obsolescence. “Guys at the manufacturers are concerned about IoT and controls and how they can develop that market, moreso than lighting itself,” says Langdon Scott of Peninsular Electric.

A pivotal time

Distributors may have A items that turn to C items or even dead stock before they realize it’s happened. Espinosa of The Lighting Co. thinks the most treacherous shift is underway in your warehouse right this moment.

“Distributors will start having obsolete inventory and don’t realize it. A items can become C items very quickly,” Espinosa says. “That issue hasn’t really kicked in yet, but it will, probably by the end of this year. They’ll see a dramatic change in pattern of the item, and unless they get a red flag to get out of the item they’ll be stuck. If we had 10 customers buying same item, and it drops down to four, at what point do you decide you’re not going to sell them anymore? That’s one thing if it’s 10 items, what if it’s thousands?”

The approach Espinosa takes to that problem can be helpful for other distributors. “We’re looking at reports, keeping a close eye on stuff. We try to improve our internal marketing. Maybe we need to market that product to those four remaining buyers. Why not discount it to those guys? We’ve done a lot of that. If we’re going to mark it down, do it for the customer, not some third party. Then as a last resort we’ll put it on the internet, when we have no local market.”

Espinosa has had success developing new niche markets outside his local area for selling oddball items. Even antiquated lamps like warm white T-12s, for example. “If you can’t sell it in your local market, it’s interesting to find someone who still values it,” he says. “It may be obsolete, but that bulb is worth $25 to someone else. You can work that to your advantage. It’s become a good stream for us. If you have it and can get it, there’s definitely some upside. You may find a church that needs a warm white U-lamp, and if you can ship to them, they’ll buy it. It’s something that we would have given away to anybody before.”

Recent data from the lighting industry reinforces the impression that LEDs are making market share gains at increasing speed across all categories, and the trend will directly affect distributors’ inventory calculus.

NEMA’s most recent lamp shipments indices show LEDs beginning to take hold in the mammoth market for linear tube lighting, T-lamps. Fluorescent T8 lamps accounted for a 67.4% share of T-lamp shipments in 2016Q1, with T12 lamps claiming a 14.5% share and T5 lamps an 11.2% share. T-LED lamps held a 6.9% share of shipments in 2016Q1, marking their first appearance in the market penetration chart.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) likewise found in its most recent CALiPER Snapshot study of the lighting products listed in its Lighting Facts database that LED replacements for linear tubes now make up the largest category in the database, with efficacy performance numbers among the best across all lighting categories.

The puzzles created by this global and industrywide shift to solid state lighting technology won’t grow simpler until the shift is past. Now is the critical time for distributors to learn to adjust.