Sponsored

Electrical distributors keep a close eye on the price of copper. That hasn’t been a happy preoccupation over the past few months. The price of copper has fallen 40% to a new six-year low and at press time is trading around $2.35 per pound.

Here’s a quick review of how we got where we are now. The short form is this: even with copper at a six-year low right now, this would not be the time to go long. Don’t buy and hold unless you have a very long horizon.

Fundamentals:

Macroeconomic headwinds

Copper has been getting hammered along with most other categories of commodities. Crude oil, gold, aluminum, coffee … they’ve all lost significant ground over the past year. One reason is the strong dollar relative to currencies of commodity exporting countries. The larger influence comes from concerns about China’s slowing economy.

Factory activity in China slowed to a 15-month low in July, a private survey of the country’s manufacturing sector showed, according to the Wall Street Journal. “The data heightened worries that China, the world’s largest consumer of raw materials, won’t be able to stem a decline in economic growth despite a series of stimulus programs launched by the government in recent months. As demand falls, many commodity exporters have failed to rein in production, stirring fears of a supply glut.”

Concern about the global economy’s near-term prospects, China in particular because it’s the largest consumer of copper and its growth since 2008 has been the key driver in recovery, suggest copper’s sluggish price supports its reputation as Dr. Copper, the PhD in Economics. The disappointing manufacturing output numbers combined with unprecedented intervention by the Chinese government to prop up stock market values have shifted global expectations about the metal’s long-run price.

A recent revision to those expectations from Goldman Sachs elicited a new round of worry among copper traders and the business media. Goldman released a report revising its three-year outlook for copper pricing significantly downward, citing primarily the prospects for economic growth in China.

“It is, in our view, highly likely that the four-year trend decline in copper prices is set to continue through at least 2018,” Goldman Sachs said in a note.

Consequently, the bank has cut its three-, six- and 12-month copper forecasts to $5,200, $4,800 and $4,800 per ton, respectively from $5,500, $5,550 and $5,200. In contrast, the industrial metal rallied to a high of over $10,000 metric ton in 2011 on huge demand from China’s housing boom.

Meanwhile there’s a surplus of copper on the world’s primary metals exchanges and world production of new copper is continuing to grow. The International Copper Study Group (ICSG) issued a report on copper production that predicted copper output will grow at a rate of 6% annually through 2018. The report also highlighted a group of countries that have never mined copper before that are planning to open mines: Afghanistan, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Fiji, Greece, Israel, Panama, Sudan and Thailand.

“By 2018, total expected copper production capacity from projects starting in these new copper mining countries could reach 150,000t/year, and capacity could continue to increase well above 1mt/year if projects planned beyond 2018 in these countries are developed,” ICSG analysts said.

Copper in History

All those trends may cause some worries about the value of your wire inventory, but it’s worth remembering that copper has played a much bigger role in human culture than the three-month contract on the London Metals Exchange can convey. Copper has a rich history of 10,000 years as one of the planet’s most useful metals. Copper’s story also has a humorous side, though lately it helps to have a taste for dark comedy. With that in mind, here’s a more or less random walk through some of the checkered history of the electrical industry’s favorite metal.

Copper Saved the Colonists

The Algonquian-speaking culture of the early 1600s around Chesapeake Bay in what’s now Virginia held copper in highest regard, not for its usefulness but for its ornamental beauty and ceremonial power. Copper was traded extensively among the tribes of the area long before the arrival of Europeans, according to the book Powhatan’s World and Colonial Virginia, by Frederic Gleach. “All copper went to the chiefs and priests, who were best able to control its power. […] Copper was widely valued among native American peoples because of its reddish color and its reflecting qualities, both of which had ritual significance.”

Copper’s value to the indigenous cultures was not lost on Captain John Smith and the other English subjects sent by the Virginia Company to establish a colony at Jamestown. Among the goods in the ships’ holds was a considerable amount of copper. At several points in their hazardous first few years at Jamestown, facing famine and foul water, the colonists traded for food with the Powhatan, on whose tribal lands they had settled. Copper was one of the most valuable trade goods, along with beads, firearms and other European technologies, so you could say copper helped keep enough of the colonists from starvation to establish the first permanent English settlement in North America.

Copper and Crime

“Listen, you crummy, flat-footed copper, I’ll show you whether I’ve lost my nerve and my brains!” Edward G. Robinson as Rico, Little Cesar (1931)

Market manipulation. In 1996, Sumitomo Corp.’s lead copper trader, Yasuo Hamanaka, was caught using a variety of different schemes to manipulate the price of copper to his advantage. One such scheme involved piling up copper in exchange warehouses, leading to a supply squeeze that drove up futures prices. This would drive up the value of copper stocks, benefiting the owners of the copper in the warehouses, among them Sumitomo.

BusinessWeek had the story: “For a decade, Yasuo Hamanaka, an assistant general manager of the nonferrous metals division at Sumitomo, was the puppet master who pulled the strings of traders in the ‘copper ring’ at the London Metal Exchange (LME), which sets copper prices worldwide, and bent a $1.45 trillion market to his will. Market sources and regulators now suspect he was trying to corner the market with the help of a coterie of brokers, traders and other accomplices, using several offshore bank accounts to bury his losses. Incredibly, his market-rigging schemes existed right under regulators’ noses.”

This was considered the most audacious trading scandal of its time. Hamanaka became known as Mr. Copper or Mr. 5%, because that’s how much of the world copper market he was said to control. Sumitomo’s losses added up to $2.6 billion. Hamanaka spent eight years in prison.

When he was released in 2005, Hamanaka told BusinessWeek he was amazed at the price of copper. It had jumped by 39% to record levels that summer, partly on concern over another copper trading scandal. Liu Qibing, a trader for China’s State Reserve Bureau (SRB), bought short positions that lost $606 million and left the Chinese government with rapidly maturing contracts for copper delivery. The rising prices reflected skepticism in the market that China could find and buy enough copper to meet the terms of those contracts. Liu disappeared. He was caught a year later in an apartment in Yunnan Province and sentenced by a Beijing court to seven years in prison, and his supervisor was sentenced to six years.

When Liu is released, he too may be amazed at the price of copper. When Hamanaka got out it had just set a new record at $4,435 per metric ton. Today, after its recent decline, it stands at $5,189 (July 27 price).

Copper theft. Even with the price at a six-year low, people still insist on risking life and liberty to creatively acquire copper and sell it for scrap. According to some reports, organized criminal networks have been built to steal copper.

This one’s a little bit personal. Several years ago one of our editors had a completely remodeled house up for sale and in between the buyer’s inspection and the scheduled closing, some freelance copper harvesting outfit broke in and took the air conditioner, the furnace core, some of the wiring and most of the copper piping. The sale still closed, though a bit later than originally scheduled, but the experience that followed that moment – “Uh…honey, where’s the air conditioner?” – summed itself up in a single question: If they had the energy, knowledge, equipment and time to get all that stuff out of the house overnight, might they not have what it takes to get a job installing them instead?

Regardless, copper theft continues to be a constant problem. In part that’s because, even with the price down around $2.35 a pound, a house-full of wire and pipe adds up, and once it gets to the scrapper it may be hard to tell where Lefty’s tangle of wire ends and the heater core of Mrs. McGillicuddy’s dead furnace begins. Serial numbers on wire and efforts in the law enforcement community to get scrappers to collect identification from sellers may help. Some jurisdictions have gone so far as to set up dedicated law enforcement units to pursue copper thieves, but they don’t seem to put much of a dent in demand. Besides, if you have an angry need churning in your head and you know there’s $3,000 worth of wire at the local Duke Energy plant, someone will give it a try, like a lovely couple in Kentucky did recently. And if there’s six miles of it along a highway outside Salt Lake City, someone’s going to try that too.

The allure of copper, not to mention its incredible usefulness in so many areas of human life, guarantees there will be demand for copper over the very long term. How that demand that will balance against supply over the near term will determine what your wire inventory will be worth tomorrow.

Answers to Questions Your Kids May Ask You About Copper

How many pennies are there in the universe?

U.S. Mint

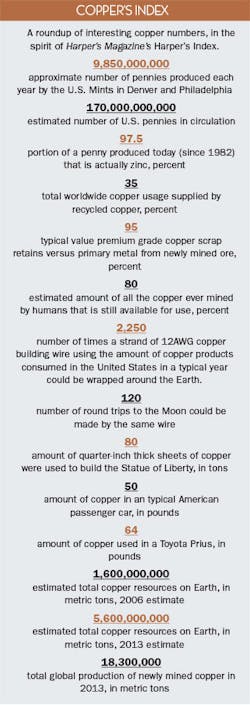

The U.S. Mints in Denver and Philadelphia produce approximately 9.85 billion pennies per year. That’s a lot of coin. And Cecil Adams with www.straightdope.com estimates roughly 170 billion pennies are in circulation, according to data he found at the U.S. General Accounting Office He reminds visitors to www.straightdope.com that pennies are actually not all copper anymore, and in fact since 1982 are really just copper-plated zinc. Most serious coin collectors know that in 1943 during World War II the government insisted the U.S. Mints make pennies out of steel instead of copper because it needed all the copper it could get for ammunition and other wartime purposes. But the steel pennies were only made for a year because people used to mistake them for dimes, they rusted too quickly and some other problems. Wikipedia says a few copper pennies were inadvertently minted and that a dozen confirmed examples exist of a 1943 copper penny. One apparently sold for $200,000 in 2004, if you believe everything you read on Wikipedia.

Who invented the American Wire Gauge (AWG)?

www.cableorganizer.com

The website, www.cableorganizer.com had a very clear explanation of the how the American Wire Gauge came into being, and a 1919 book by Rome Wires and Cables provided a more technical explanation. We will offer up the www.cableorganizer.com summary for our purposes in this sidebar:

“The American Wire Gauge (AWG), a wire-sizing standard also known as the Brown and Sharpe wire gauge, is used in North America to measure and regulate the thickness of conductive wires made from nonferrous metals. AWG is not to be confused with the Washburn and Moen (W&M), US Steel, or Music Wire gauging methods, which are used only for steel-based wire.

“AWG was developed in 1856 by J.R. Brown and Sharpe, a small firm in Providence, Rhode Island that specialized in the crafting and repair of watches, clocks, and mathematical instruments. That same year, Lucien Sharpe presented the new system to the Waterbury Brass Association. Convinced that Brown and Sharpe’s gauging system would greatly improve uniformity throughout the wire manufacturing industry, Waterbury Brass Association made a movement to adopt the standard. By February of 1857, eight major American manufacturers had signed resolutions to adhere to the Brown and Sharpe gauge standard; the following month, a nationwide circular was distributed, introducing the new wire gauge standard to the American public.”

How much copper wire is in a wind farm?

www.copper.org

According to the Copper Development Association, “Copper plays a crucial role in the delivery of wind energy, based on its high-conductivity, low electrical resistance and resistance to corrosion. Some wind farms contain more than 300,000 feet of copper wire. Electricity generated through wind power flows through insulated copper cables to a copper-wound transformer. Underground copper cables collect the electricity from the base of each tower and deliver it to a substation that transmits it to the utility grid.”

How much copper is consumed in the United States each year?

www.copper.org

The good folks as the Copper Development Association (CDA), New York, have collected quite a few interesting facts about copper. Here’s what they have to say about #12 AWG building wire. “The amount of copper products consumed in the United States in a typical year would make a size 12 wire that could encircle the Earth 2,250 times or make 120 round trips to the Moon.”

How much copper is in the Statue of Liberty?

www.copper.org

Legend has it that when the Statue of Liberty was first built, its copper sheathing shone like a bright new penny when the sun reflected on it. The CDA says that when the Statue was built in 1886, “Some 80 tons of copper sheet, originally about a quarter-inch thick, were cut into 300 odd pieces and then hand hammered -- a process called repoussé. The hammering reduced them to about 3/32nds of an inch thick… It was the largest use of copper in a single structure at that time.”

What famous statue from ancient times was made of copper?

www.copper.org

That would be the Colossus of Rhodes, a statue that according to Greek legend stood across the entrance to Rhodes harbor. CDA says no trace of it remains because it was recycled to make other items.

How do spy agencies use copper to protect their data?

www.coppermatters.org/copper-facts

Here’s a fascinating bit of copper trivia for espionage buffs from www.coppermatters.org: “Not only can copper be used to send information, but it can also be used to prevent signals traveling where they are not wanted. The National Security Agency buildings at Ft. Meade, Maryland, are sheathed with copper to prevent unauthorized snooping. Even the windows are fitted with copper screens. The copper blocks radio waves from penetrating into or escaping from spy operations. Copper sheathing is also used in hospitals to enclose rooms containing sensitive equipment like CAT scan, MRI and X-ray units to prevent problems related to the entrance or emission of errant electromagnetic radiation.”

How much copper is an electric vehicle?

www.coppermatters.org & U.S. Global Investors’ Frank Talk blog

According to www.coppermatters.org, the Toyota Prius uses 64 pounds of copper in every car. This website also says there’s more than 50 pounds of copper in a typical American made automobile -- about 40 pounds for electrical and about 10 pounds for nonelectrical components.

U.S. Global Investors’ Frank Talk Blog had this to say about the expected copper consumption of Elon Musk’s Tesla Motors $5 billion factory near Reno, Nev. “When production begins on its lithium-ion batteries, it will consume biblical amounts of base metals and other raw materials — so much, in fact, that some analysts question whether world supply can meet demand. “Besides needing a constant stream of lithium and nickel, the factory will consume a staggering 17 million tonnes of copper.”

— Jim Lucy, Chief Editor