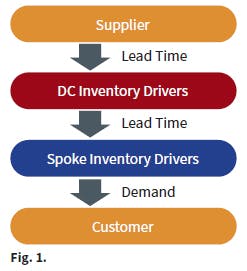

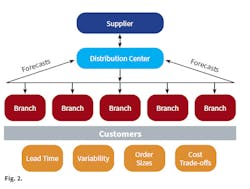

A “hub & spoke” distribution network can have some major pitfalls. One is typically a lack of true network optimization because stocking and replenishment strategies are applied to one echelon without regard to the other(s) (See Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Another pitfall is the reliance on demand forecasting and its inherent variability. There are some potential negative consequences, such as excess inventory in the form of redundant safety stocks at both hub-and-spoke. I have also seen stock-outs at a spoke even though adequate inventory exists in the distribution network, and the distributor thought the service between DC (distribution center) and spoke was acceptable. MCA Associates have also seen variances in what distributors order and the actual demand, due to demand variability.

Demand – the rate of product flow out of the DC

Demand variation – fluctuation in the rate of product flow out of the DC, from one period to the next

Lead time – time between ordering product and having it available to fill demand

Lead time variation – fluctuation of the lead time, from replenishment order to replenishment order

Replenishment review frequency – the frequency that the DC’s inventory position is checked to see if a new replenishment order is needed

Replenishment order strategy – the DC’s supply objective, a trade-off between carrying inventory, transportation and purchase cost

Service level goal — the DC’s service commitment to its internal and its own external end-use customers

Inventory position — the DC’s available stock (on-hand, on-order, backorders, commitments)

The relationship between the DC and the spoke depends on the spoke’s own demand forecast, order frequencies (related to stock-transfer frequency), safety stock protection and other ordering rules that may have a bearing on the spoke’s replenishment order quantities. Some issues emerge here:

- The appropriate “measure of demand” signaled to the DC, from the spoke, and how should it be forecast

- Accounting for demand variation

- The effect of larger-than-necessary replenishment orders from the supplier to the DC and their impact on the overall supply chain strategy

- The optimal service level goal between the DC and its “customers” —the spokes

- Factoring in the spoke’s inventory position into the DC’s replenishment decisions

- Replenishment review frequency and the DC’s service level goals impact inventory and service levels at the spoke

- When there’s a limited supply of product at the DC, the strategies for product allocation to the spoke

- Customer expectations for the same service level from the DC, when the DC is servicing its own “end use customers”

- The role that the DC’s external supplier’s lead time and lead time variation play in the spoke’s replenishment strategy

Lack of visibility up the demand chain

When a spoke seeks to replenish itself, it’s blind to suppliers beyond the DC. The spoke ignores any lead-times other than its own — the lead time from the DC. The spoke may also assume that the DC will completely fill its replenishment orders each and every time. And depending on your ERP system, the spoke may not have any visibility into the DC’s inventory balances.

Lack of visibility down the demand chain

Similar to the case above, when the DC seeks to replenish itself, it may be oblivious to customer demands beyond those of individual spokes and/or have no visibility into the spoke’s inventory balances.

Demand distortion

Because the DC and spoke create independent demand forecasts (based on their own immediate “customer’s” demands), distortions in demand and peaks and valleys often result in too much inventory at the DC.

Total distribution network costs

If one or more of the spoke’s inventory drivers are modified, the cost implications may be readily apparent at the spoke, but not readily visible to the DC. The impact becomes strictly focused on one single echelon.

No linkage between safety stocks

The DC and each spoke protect themselves independently, so any desire to optimally balance inventory is made more problematic. This lack of cohesiveness is caused by independent decisions as to how inventory will be managed, either at the DC or spoke.

In the third part of this series, we will explore the difference between “push” and “pull” inventory management strategies.

Howard Coleman and his team at MCA Associates help distributors and manufacturers implement continuous improvement solutions focused on business process re-engineering, inventory and supply chain management, sales development and revenue generation, information systems and technology, organizational assessment and development. MCA Associates may be contacted at 203-732-0603, or by email at [email protected]

Editor's note: This article and the first part of this series are also available in a digital format by clicking here.

About the Author

Howard Coleman

Howard Coleman and his team at MCA Associates (www.mcaassociates.com) helps distributors and manufacturers implement continuous improvement solutions focused on business process re-engineering, inventory and supply chain management, sales development and revenue generation, information systems and technology, organizational assessment and development. MCA Associates may be contacted at 203-732-0603, or by email at [email protected].